Revenge bedtime procrastination is real. It refers to the idea of people postponing the act of going to bed and shortchanging sleep to indulge in leisure activities (like binge-watching web series) they don’t have time for during the day. Most of us fall prey to it and believe that we can catch up on the lost sleep later. But regular sleep deprivation can spell trouble. While many studies have been conducted to examine the health effects of the duration of sleep, few have explored the impact of sleep timing. A 2021 study identifies the ideal hour for slipping into slumber, its effects on cardiovascular health (an important marker of metabolic health) and the connection between sleep and circadian rhythm (the body’s internal clock that controls the sleep-wake cycle).

The optimum time for sleep

The latest research published in the European Heart Journal has identified a sweet spot for sleep – 10 to 11 pm. As per a peer-reviewed article, over 88,000 adult participants were tracked for six years. The study attempted to find out how different bedtimes affect heart health. They wore accelerometers on their wrists for a week, which helped to accurately ascertain the time of their sleep commencement and waking. In the follow-up of 5.7 years, it was uncovered that 3,172 participants underwent heart attacks, strokes or heart failure, and their occurrence was highest in people who slept at midnight or later.

The incidence of these cardiovascular conditions was the least in people who slept between 10 p.m. and 10.59 p.m. After considering a number of factors, such as body-mass index, gender, age, smoking status, socioeconomic status, blood pressure, sleep irregularity and classifications, like being a night bird or an early riser, it was found that going to bed consistently at midnight or later was still associated with maximum risk of cardiovascular disease. This risk was more distinct in women. This elevated risk was attributed to the potential differences in the way the endocrine system in men and women reacts to an imbalance in the circadian rhythm. Interestingly, the study found that more men were at a higher risk when they slept earlier, i.e., before 10 p.m.

Out 3172 participants (3.58%) who were diagnosed with cardiovascular disease, 1371 (43%) displayed a sleep onset time after midnight; 1196 (38%) slept between 11:00 p.m. and 11:59 p.m.; 473 (15%) fell asleep between 10:00 p.m. and 10:59 p.m.

Compared to the zone of sleep onset from 10 p.m to 10.59 p.m. it was found that

Those who slept before 10 pm were at 24% higher risk of heart disease

Those who slept between 11 and 11.59 pm were at 12% higher risk of heart disease

Those who slept at midnight or later were at 25% higher risk of heart disease

One of the surprising findings of this study, contrary to the ‘early to bed convention’ is that an early bedtime of pre-10 pm is riskier than sleeping at 10 pm. “The ideal time to go to sleep is at a specific point in the body’s 24-hour cycle and deviations may be detrimental to health. While we cannot conclude causation from our study, the results suggest that early (before 9 pm) or late bedtimes (after 11 pm) may be more likely to disrupt the body clock, with adverse consequences for cardiovascular health,” says Dr David Plans, co-author of the published study. According to him, the riskiest time was post-midnight, since it plausibly lessens the chances of waking up in the morning to see the daylight, when the body clock is realigned. Dr Harley Greenberg, the head of the Critical Care and Sleep Medicine division of New York-based popular health division also infers that detrimental health effects are correlated with a sleep roster that is misaligned with our biological clock.

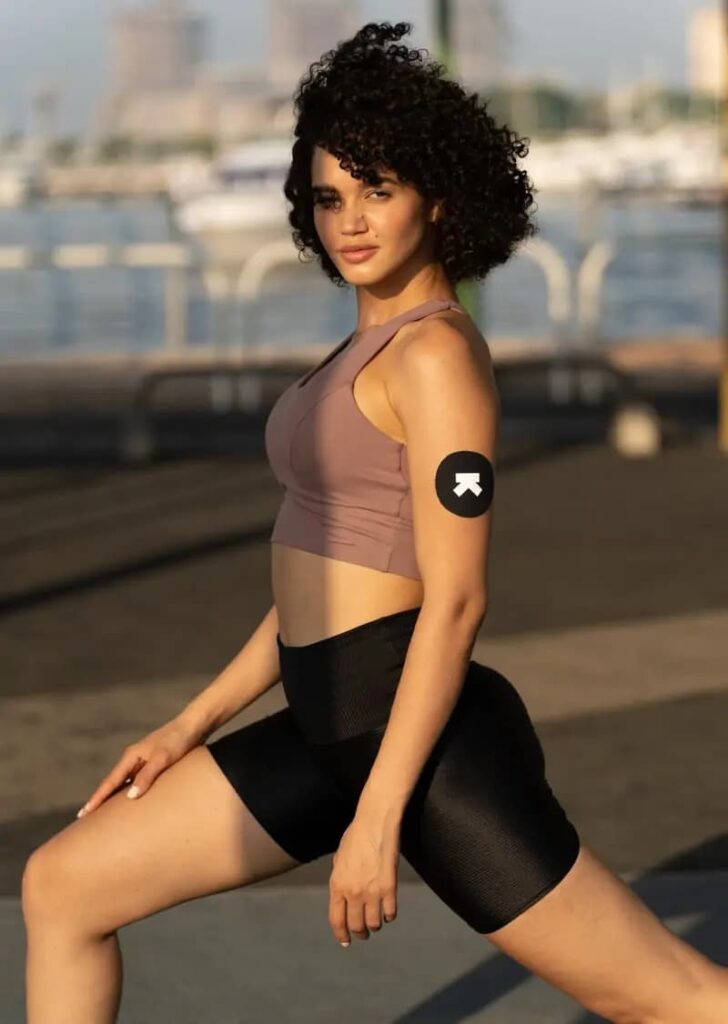

The authors of the study assert that the results of the study mandate more research into sleep timing as a determinant of cardiac ailments. They also make a case for monitoring sleep data with wearables in relation to heart health.

What the findings mean: the role of circadian rhythm

The circadian rhythm is another name for our body’s biological clock. In Latin, it translates into ‘around or approximately’ (circa) ‘a day’ (diem). The visual signal of light—its intensity/kind of light, along with the duration and time of exposure—facilitates this process. Light travels through the eye to the brain. The brain receives cues from the environment, prompts certain hormones and steers the metabolism to help you stay awake during the day and put you to sleep at night. Other determinants of the body’s internal clock include melatonin, the sleep hormone, physical activity and age.

Research suggests that insufficient sleep or poor quality of sleep over a period of time can raise your odds of metabolic dysfunction. Metabolic health refers to having ideal levels of blood sugar, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, blood pressure and waist circumference, without using medications. Mounting evidence shows that the disruption of the body’s circadian rhythm by staying awake late into the night can lead to insulin resistance (when the cells don’t respond efficiently to the hormone insulin), resulting in a gradual rise in glucose levels. Research suggests that circadian impairment may affect glucose metabolism, leading to elevated glucose levels and increased risk of diabetes. The imbalance in the circadian cycle is caused by low nocturnal melatonin secretion. Darkness triggers the pineal gland to generate melatonin, while light brings this production to a halt. Melatonin synchronises our sleep-wake cycle with the day and the night and sets the stage for the transition to sleep. It is responsible for consistent and good sleep. Low sleep levels can lead to increased circulating cortisol (a stress hormone), which results in gluconeogenesis (production of glucose from non-carbohydrate sources) and, in turn, affects glucose regulation.

Experts suggest that each stage of sleep is tethered to certain functions. Sleeping in sync with the circadian rhythm gives you the benefits of both REM (rapid eye movement) and NREM (non-rapid eye movement) stages of sleep.

When you fall asleep, you enter light stages of Deep Sleep (stage I and stage II), where the brain and heart slow down. After 20 minutes of falling asleep, you tend to fall into the later stages of Deep Sleep (stage III and stage IV). After about 70 minutes, you go into REM sleep. Each cycle of sleep (Deep + REM) lasts about 90 minutes. The first half of the night is predominantly NREM, and the second half is REM sleep. Cortisol production (responsible for alertness during the day) is suppressed at night and melatonin is secreted between 2 a.m. and 4 a.m. One of the important functions of sleep is to revive the brain’s chemical balance. Not sleeping in accordance with the circadian rhythm can be detrimental to this repair process. Even if you sleep for the same amount of time, the body doesn’t go through the vital repair process.

Conclusion

A 2021 study suggests that sleeping between 10 p.m and 11 p.m. makes for an optimum bedtime, as it lowers the risk of heart disease. The findings indicate that the risk is higher in women. The results show that earlier or later bedtimes may be more likely to disrupt the body clock or the circadian rhythm. Research also suggests that disruption of the circadian cycle affects cardiovascular health and elevates blood sugar levels, both of which are markers of metabolic health. Experts confirm that sleeping in sync with the circadian rhythm gives you the benefits of both REM (rapid eye movement) and NREM (non-rapid eye movement) stages of sleep. The circadian rhythm regulates your mental and physical functioning, and good sleep hygiene can go a long way in boosting your cardiac and overall metabolic health. More research is required to understand the correlation between this hour of sleep and cardiac risks/heart health.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are for general information and educational purposes only. It neither provides any medical advice nor intends to substitute professional medical opinion on the treatment, diagnosis, prevention or alleviation of any disease, disorder or disability. Always consult with your doctor or qualified healthcare professional about your health condition and/or concerns and before undertaking a new health care regimen including making any dietary or lifestyle changes.

References

- https://www.webmd.com/diabetes/sleep-affects-blood-sugar

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2021/11/211108193627.htm

- https://www.sleepfoundation.org/melatonin

- https://www.mid-day.com/mumbai-guide/things-to-do/article/why-be-an-early-riser-23200912

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4667373/