Glucose is the fuel of the brain and it can be reflective of our stress, irritability and anxiety amid other emotional states. The graph of our glycemic ups and downs can serve as a mood board of sorts. Let’s understand how glucose is metabolised in our body before we explore the connection between blood sugar and mood.

Highlights

- The interaction between glucagon and blood sugar ensures stable blood glucose levels in the body and the brain,

- Research suggests a correlation between higher glycemic variability and lower quality of life and negative moods,

- Dehydration has a bigger influence on blood glucose levels than most people realise. Even a little dehydration can cause blood glucose levels to spike.

Glucose Metabolism

Insulin is a hormone created by the pancreas that controls the amount of glucose in a person’s bloodstream at any given moment. It helps store glucose in the liver, fat and muscles, and regulates the body’s metabolism of carbohydrates, fats and proteins. After eating, blood glucose levels rise. Insulin released by the pancreas helps the cells to absorb blood glucose for energy and storage.

With this absorption, glucose levels in the bloodstream begin to decline. The pancreas then produces glucagon, a hormone that prompts the liver to release stored sugar. This interaction of glucagon and blood sugar ensures stable blood glucose levels in the body and the brain. The cells of individuals who have insulin resistance don’t respond well to insulin, preventing glucose from entering them with ease. The glucose level in their blood rises over time even as their body produces more insulin, as the cells resolutely resist insulin.

There are three sources from which we get circulating glucose: intestinal absorption during the fed state, glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. The rate of gastric emptying is what determines the speed at which glucose appears in circulation during the fed state. Other sources of circulating glucose mainly come from hepatic processes – glycogenolysis, the breakdown of glycogen (glucose in the polymerised storage form) and gluconeogenesis, which is the formation of glucose from lactate and amino acids during the fasting state. Both glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis are partly controlled by glucagon. During the first 8–12 hours of fasting, glucose is made available primarily by glycogenolysis. During longer fasting periods, glucose produced by gluconeogenesis is released from the liver.

How blood glucose affects mood

1. Blood Glucose chaos: Blood glucose chaos (furthered by author, Dr Kelly Brogan, MD) refers to ways in which blood sugar imbalance can impact our mental and emotional state. Dr Brogan shines a light on depression beyond a chemical imbalance and makes a case for directing attention to the body’s ecosystem, i.e., gut health, inflammation, blood glucose and thyroid functioning. It’s important to understand blood glucose rises and crashes before examining the relationship between blood glucose levels with mood.

2. Non-diabetic Hypoglycemia: When it comes to blood glucose imbalance, we tend to overlook hypoglycemia, a condition where blood glucose levels drop below the normal range (70 — 110 mg/dL). Some factors that could contribute to non-diabetic hypoglycemia include diet, medication, excessive alcohol consumption, adrenal and pituitary gland disorders and kidney problems.

There are two types of non-diabetic hypoglycemia: reactive hypoglycemia and fasting hypoglycemia. Reactive hypoglycemia, or postprandial hypoglycemia, is a glucose crash that occurs within four hours of a meal. This is different from fasting hypoglycemia, which is a drop in glucose levels as a result of fasting.

According to Dr Brogan, blood sugar chaos sparks the cycle that leads to reactive hypoglycemia. It begins with eating high-carb foods, which disintegrate into glucose that floods the bloodstream. Blood sugar levels rise and the pancreas secretes insulin to counter the situation as explained in the process of glucose metabolism. A blood glucose plunge follows.

It brings in its wake fatigue, brain fog, disorientation and ‘depression’-like symptoms. The hormonal reaction to reduced blood glucose includes the speedy discharge of epinephrine and glucagon, accompanied by the secretion of cortisol and growth hormone. The cortisol deluge makes you feel anxious, ‘hangry’ and shaky and the sugar cravings strike, usually leading to the intake of sweets, and processed foods.

Blood glucose surges again and the cycle continues. With insulin resistance, the cognitive and emotional manifestations are aggravated. Since reactive hypoglycemia doesn’t get as much attention, the blood glucose chaos theory proposes that many of its symptoms are masked as those of mental health issues.

The ‘hanger’ and cravings that one regularly experiences in reactive hypoglycemia are telling signs of chronic blood glucose instability. This, in addition to insulin resistance, which develops as a result, can pave the way for type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and even the onset of Alzheimer’s at a later stage. Glycemic highs and lows have also been linked to symptoms of mental health disorders such as chronic anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder and aspects of ADHD.

While the exact cause of reactive hypoglycemia is unclear, experts attribute it to the kind of food consumed and the time it takes for the food to digest. It is most common in people who go long hours without eating, have disordered eating cycles (starvation/bingeing), those on restrictive diets and whose diet is high in refined and processed carbohydrates.

3. Non-Diabetic Hyperglycemia: What happens when blood glucose levels spike? Hyperglycemia, or high blood glucose, occurs when there is too much sugar in the blood (more than 180 mg/dL, 1–2 hours after a meal, and 125 mg/DL while fasting). Like low blood glucose, hyperglycemia can look a lot like mental health conditions, especially in non-diabetic people, since we don’t immediately think of blood glucose in relation to feelings of anger, sadness, tension, and lethargy.

While most psychiatric symptoms, such as delirium and confusional states, have been associated with hypoglycemia, studies have found acute hyperglycemia to produce episodes of psychosis. Hyperglycemia goes hand-in-hand with diabetes, though it can also affect people without diabetes. Non-diabetic hyperglycemia may occur suddenly due to a major illness or injury and also develop over time as a result of chronic disease.

Endocrine conditions – such as Cushing’s syndrome which causes insulin resistance, pancreatic diseases – such as pancreatitis and cystic fibrosis), surgery and medications – such as steroids and diuretics are some ways in which hyperglycemia can affect people without diabetes.

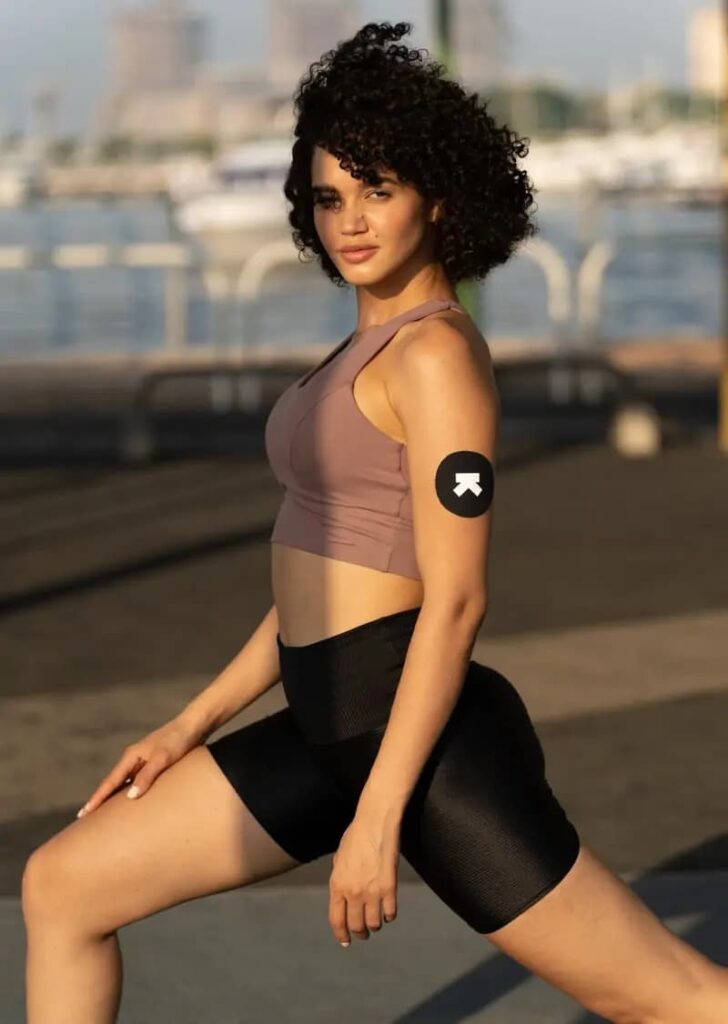

4. Glycemic Variability: Glycemic variability refers to the fluctuations in blood glucose levels defined by measuring said fluctuations over a given time interval. It is typically measured by self-monitoring of blood glucose. When glucose levels vary at different points in time, they offer important insights into our bodies.

The metric of glucose variability helps identify these internal oscillations in blood glucose levels. Research suggests a correlation between higher glycemic variability and lower quality of life and negative moods. Impaired glycemic control has also been linked with anxiety. Maintaining your blood glucose range in a safe zone can help you address symptoms of anxiety. While mental health conditions such as depression are common among people with diabetes, additional studies are needed to establish its relationship with glycemic control. On the other hand, good glycemic control has been associated with improvements in mood and an overall sense of well-being.

5. Stress: Stress is often chalked down to emotional problems such as anxiety and worry, having nothing to do with physiology. But stress can also be physical, nutritional and chemical. When we’re under stress, the adrenal glands trigger the release of glucose stored in various organs, leading to elevated levels of glucose in the bloodstream. Adrenaline also produces symptoms such as sweaty palms and accelerated heartbeat and can make us anxious and irritable. When these warning signs go unaddressed, it sets off the release of cortisol.

Cortisol is the body’s stress hormone, which is related to the flight-or-fight mode—to help control such things as mood and fear. When paired together, adrenal and cortisol can be a recipe for anxiety. Renata Belfort De Aguiar, an assistant professor of medicine in endocrinology at the Yale School of Medicine, suggests that conversely, an emotional imbalance can also lead to fluctuations in blood glucose. She tells a publication that stress could impact your blood glucose levels by altering your habits. It could push you to eat more and exercise less and, thus, affect blood glucose levels.

6. Stress and lifestyle: Since stress and blood glucose fluctuations are so inextricably linked, let’s look at some habits that play into an overall sense of feeling stressed out:

- Skipping breakfast: A good breakfast—one that is rich in fibre, complex carbohydrates, and protein—can help replenish our glucose levels and maintain a steady blood glucose level throughout the day. When we skip breakfast, the pancreas produces glucagon, which then signals the liver to release glycogen, which is then converted to glucose. This means that skipping breakfast can actually elevate and destabilise our blood glucose levels.

One study showed that skipping breakfast creates dramatic blood glucose highs and lows, while another study found that those who skip breakfast even once a week are at an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

- Late-night eating: Is your bedtime erratic? Are you given to late-night snacking or having a meal just before hitting the sack? These could be major contributors to any stress you experience. A 2020 study states that late-night meals can cause a spike in blood glucose levels while you sleep and, according to the American Diabetes Association, they remain elevated in the morning.

- Not sleeping enough: Lack of quality sleep is known to throw blood glucose levels out of whack and has a negative effect on insulin resistance in particular. According to this study, lack of sleep triggers the release of cortisol, the stress hormone, creating higher blood glucose levels.

- Not drinking enough water: Dehydration has a bigger influence on blood glucose levels than most people realise. Even a little dehydration can cause blood glucose levels to spike, creating a dangerous cycle: the kidneys make you urinate to flush out excess glucose from the body, but the more you urinate, the more dehydrated you become. Water makes up 50–60% of body weight in women and 60–65% in men, so every biological function depends on the availability of water.

7. Diabetes distress

It is common for diabetes patients to experience a range of highs and lows. Feelings and mood swings may be affected by blood glucose levels. Negative feelings and reduced quality of life can result from poorly managed blood glucose. Research suggests that a debilitating side-effect of therapy in diabetic patients, recurrent hypoglycemia (RH), has pronounced effects on memory and cognitive processes, leading to mood disorders and anxiety.

Living with diabetes may also lead to a mental health condition called diabetes distress, which is an emotional state that has elements of depression, anxiety, guilt and denial. According to a 2019 study, depression affects 25% of the diabetic population. Hyperglycemia has also historically been associated with anger and sadness, while hypoglycemia is associated with nervousness. According to another study on diabetes distress, major depressive disorder (MDD), is a debilitating condition. It permeates all aspects of life, and affects the diabetic population about three times more than it does the general population.

Six ways to optimise glycemic control

Our brain runs on glucose. Therefore, managing blood glucose levels is crucial for our overall emotional and physical well-being. Here are some lifestyle changes that can go a long way in stabilising and maintaining blood glucose levels.

1. Diet: As we’ve already seen, food majorly influences the blood glucose levels of the body. Cutting down on refined and processed carbohydrates, alcohol and caffeine, and increasing high-fibre foods (such as fruits and vegetables) and starchy foods with a low glycemic index (such as lentils, parboiled rice and oatmeal) can help maintain blood glucose levels. Eating five to six small meals a day as opposed to three large meals is also recommended.

Research tells us that there is a close connection between depression, abdominal obesity and blood glucose imbalance. Thirty-six per cent of depressive syndromes are considered ‘atypical depression’, which is characterised by carb craving, fatigue, bodily heaviness and interpersonal sensitivity.

2. Exercise: Regular exercise can help achieve and maintain a moderate weight, which increases insulin sensitivity. This allows cells to better use available glucose in the bloodstream. Some useful forms of exercise that can be easily included on a regular basis include running, brisk walking, swimming, biking and dancing. According to a study, an increase in non-exercise physical activity can enhance glycemic control.

3. Managing stress: We’ve already looked at the close relationship between stress and blood glucose levels. Managing stress, therefore, is vital to glycemic control. Studies suggest that exercises and relaxation techniques, such as mindfulness and yoga, can even correct insulin secretion issues in chronic diabetes.

4. Monitoring Glucose Levels: Closely monitoring blood glucose every day and maintaining a log can go a long way in managing levels. It can also help understand how the body responds to specific foods.

5. Drinking water: Drinking enough water helps the kidneys flush out excess glucose and maintain optimal blood glucose levels. One study found that those who drank more water had a lower risk of developing high blood glucose levels.

6. Getting adequate sleep: Sleep deprivation decreases the release of growth hormones and increases the production of cortisol, both of which play a role in blood glucose management. It is also worth noting that the right amount of sleep is about both quantity and quality. For optimal blood glucose levels, an adequate amount of high-quality sleep is a must.

Conclusion

Growing evidence suggests that there is a close relationship between fluctuating blood glucose levels and mental health. Blood glucose chaos makes way for a pattern of reactive hypoglycemia, a condition where blood glucose levels drop too low in non-diabetic individuals. It leads to feelings of ‘hanger’, irritability and anxiety. Glycemic highs and lows have been linked to symptoms of mental health conditions such as chronic anxiety and depression, with 25% of the diabetic population diagnosed with depression. Good glycemic control can play a major role in improving mood and an overall sense of mental and emotional well-being. Some ways to optimise glycemic control include a high-fibre diet, regular exercise, managing stress, drinking water, getting a good amount of high-quality sleep and keeping a close eye on blood glucose levels.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are for general information and educational purposes only. It neither provides any medical advice nor intends to substitute professional medical opinion on the treatment, diagnosis, prevention or alleviation of any disease, disorder or disability. Always consult with your doctor or qualified healthcare professional about your health condition and/or concerns before undertaking a new health care regimen including making any dietary or lifestyle changes.

References